Introduction:

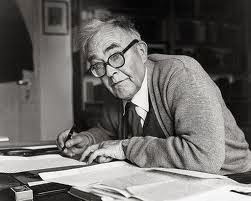

During my second year of Seminary, I had the pleasure of

taking a yearlong “theology and ethics of Karl Barth” course at Pittsburgh

Theological Seminary taught by Dr. John Burgess. The year accounted for three credits hours in

which we covered Karl Barth’s “Church Dogmatics Volume 3: The Doctrine of

Creation Part 4.” The setup of the class was to read anywhere from 25-40 pages

of Barth a week and produce a detailed outline of the material in the readings.

We then would meet once a week to discuss the readings. At the end of the

course, we were asked to prepare a 20-page paper that covered a main theme in

the Church Dogmatics Volume. This series of blogs consists of sections from my

paper that I wrote for the course. As you will see in the posts, I was

specifically impressed by Barth’s discussion of ethical issues in the light of

the Command of God and what he calls the exceptional case to that command.

There are many other things that I loved in this volume that are not covered in

these post, and I am in no way claiming to have fully comprehend what Barth is

getting at, I just want to share some of my thoughts in hope to continue my

theological pursuit after seminary!

The last issue that will be addressed in the attempt

to understand Barth’s view of the Command of God “thou shall not kill”, is the

question can there be a just war? For Barth, if there is such a thing as a just

war, then the restrictions would be stricter than those placed on suicide,

self-defense, and capital punishment. Barth understands war as an action in

which the nation and all its members are engaged in killing. What Barth means

by this is that though the citizens may not be a part of the military and

involved in the actual killings, all who desire or permit the war are also

involved in it.[1] The only way this would not be the case is in

the rare occasion that the citizens were to wage war against the service of

their country. But since this is often not the case, when loyalty and devotion

to a country is taken into account, it is safe to say that all people are in

some way involved in a war. Barth suggests that killing in war calls into

question the whole morality and obedience to the Command of God. It certainly

raises the question among Christians, “how can a Christian believe and pray

when at the climax of this whole world of dubious action there is a brutal

matter of killing?[2]” In the light of the Command of God and its

demand for the respect of human life, war seems to fall very short for many

reasons, an obvious one being that war does not make a person better.

The first

essential notion Barth wants his reader to understand is that war should not,

on any account, be recognized as normal for the Christian view of a just state.[3] But Barth does not shy away from the fact

that the state possesses power and must be able to exercise it. Nevertheless,

according to Barth, Christians must push for the state to use their power only

in the case of an ultimate ultimatum. The Christian Church must challenge the

state in every way in properly determining and judging what qualifies as the

ultimate ultimatum.[4]

Barth pushes for the Church to have an active voice in the state’s process of

determining the ultimate ultimatum for justification of war. If the Church

fails to step into this role then they cannot expect their voice to have any

meaning in the state’s darkest hour. Guidelines are given by Barth as to what

Christian ethics is to emphasize. The Church should push to ensure that it

never is the case that the state’s motivation and focus in war are the

annihilations of human life.[5] They should rather be concerned with

fostering life of all parties involved in the dispute. There should also never

be an argument that suggests that annihilating life is a process of maintaining

and fostering it. This type of biological perspective is corrupt and cannot

serve as a normal rule of ethic. Barth makes his point clear when he says,

“According to Christian understanding, it is no part of the normal task of the

state to wage war; its normal task is to fashion peace in such a way that life

is served and war kept at bay.[6]”

However,

as displayed earlier and championed by Barth, absolute principles are not ideal

in approaches to ethics and so he sees and identifies the mistakes of pacifism.

The major objection regarding pacifism is, “in its

abstraction of war, it fails to understand it as in relation to the peace which

precedes it.[7]” Barth is not concerned with absolute

principles or rules against war, but the motivation and reason behind the

state’s decision. If the motivation is wrong, for example, when the interest of

the state is bearing capital, rather than preserving the life of humanity,

Christian ethics demands an outcry from the Church.[8] On the other hand, Barth seems to suggest

that if there was a war in which motivation rested in the fact that the state

was seeking to preserve the life of humanity then it would not be against the

Command of God. This comes from Barth’s concept of freedom of the Command of

God to reign in the lives of believers.

Peace is

the real emergency in which all the time, power, and ability of Christian

ethics is devoted. The justifiable war must be focused on the restoration of an

order of life that is meaningful and just.

The Church should be encouraging the state to do its best for justice

and peace, to look for solid agreements and alliances with international courts

and conventions, to push for all nations to display openness, understanding and

patience towards others, and educate the young people to lead them to prefer

peace over war. All this concludes that the Church should not preach pacifism,

but instead encourage peace, and only treat war as the last resort.